We all know that Labor Day happens on the first Monday in September. For many of us, it’s a break from work or school and a last chance to squeeze in a vacation before the fall work grind arrives – but the holiday has a lot of meaning. The history of Labor Day is, not surprisingly, influenced by organized labor in more ways than one. From its murky beginnings to its lasting legacy, check out these nine cool facts about Labor Day.

1. The founder of Labor Day is disputed

There’s a dispute as to who founded Labor Day. Some people maintain that Matthew Maguire proposed it in 1882 when he was secretary of the Central Labor Union of New York. Other people claim that Peter J. McGuire from the American Federation of Labor proposed a Labor Day holiday in May 1882.

2. The first Labor Day celebration almost didn’t happen

On Tuesday, September 5, 1882, the Central Labor Union celebrated Labor Day. The celebration included a parade, a picnic, a concert, and speeches. However, it almost didn’t happen. At first, only a few marchers showed up for the parade, and they had no music to march to.

William McCabe, the parade organizer was determined to hold the parade, despite the suggestions from the spectators to give up. Fortunately, Matthew Maguire told McCabe that almost 200 workers from the Jewelers Union of Newark Two had just arrived with a band.

The jewelers joined the parade and the workers marched through the streets, eventually joined by the spectators. By the end of the day, roughly 10,000 people took part in the festivities and laid the foundation for Labor Day across the U.S.

3. Oregon was the first state to legislate Labor Day

Though Oregon wasn’t the first state to introduce a Labor Day bill (New York was), it was the first state to pass a bill supporting Labor Day. On February 21, 1887, Oregon made Labor Day a state holiday.

4. Labor Day might not have been a federal holiday if not for the Pullman Strike

Seven years after Oregon made Labor Day part of its state calendar, the federal government made Labor Day a national holiday. The federal government passed Labor Day legislation party to appease railroad workers in the wake of the Pullman Strike.

In 1894, the Pullman Company, located in Pullman, Chicago, cut its workers wages but didn’t reduce its rent, gas, or water rates in the company town. Naturally, this angered the workers, who demanded that the owner, George Pullman, lower the rates. Pullman refused, and the workers organized a strike, shutting down much of the rail traffic west of Detroit.

President Grover Cleveland ordered the U.S. Army in to stop strikers from obstructing the trains. Not surprisingly, violence broke out between the strikers and the soldiers. To smooth over relationships between organized labor and the federal government, Cleveland pushed for Labor Day legislation.

5. Labor Day almost was going to be in May

When the federal government was deciding which day to choose for Labor Day, President Cleveland strongly objected to the idea of celebrating it on May 1, a day commonly known as International Workers Day. He was afraid that holding Labor Day at the beginning of May would encourage more protests like the Haymarket Affair.

The Haymarket Affair happened on May 4, 1886, in Chicago at Haymarket Square. Workers were striking for an eight-hour day and in protest of police killing several workers the day before. When officers went in to break up the crowd, someone threw a dynamite bomb into the crowd, killing seven police offers, four civilians, and wounding dozens.

Cleveland wanted to avoid those kinds of protests as well as socialist and anarchist sympathizers.

6. Labor Day celebrations were outlined in legislation

Labor Day parades happen ever year, and that’s the way the holiday was legislated. The reason for the parade is to show the strength and spirit of the workforce. It’s a morale booster and serves to show off the economic power of cities, and the nation as a whole.

7. “Labor Sunday” is actually a thing

In 1901, the American Federation of Labor deemed the Sunday before Labor Day Labor Sunday. Labor Sunday is dedicated to the spiritual and educational aspects of the labor movement.

8. Wearing white after Labor Day was a rule likely created by the upper class

In the wake of the Civil War, old-money Americans felt threatened by new-money Americans (those who didn’t have the prestigious lineage or upbringing traditionally associated with the upper class but had the money to run in the same social circles). To weed out the true upper class from the new wannabes, someone decided that women shouldn’t wear white after Labor Day.

Women usually wore white during the summer months because it was a lighter, cooler color. White was socially acceptable at resorts and on vacations, but for a night out at the opera or for a classy dinner party it was a no-no. Since Labor Day marks the unofficial end of summer and a time when Americans return to work or school, it made sense to deem white unacceptable after it.

Fortunately, it’s not as big of a deal to wear white after Labor Day today, though there will always be that one person who smugly informs you that you’re not supposed to do it.

9. The eight-hour work day didn’t appear all at once

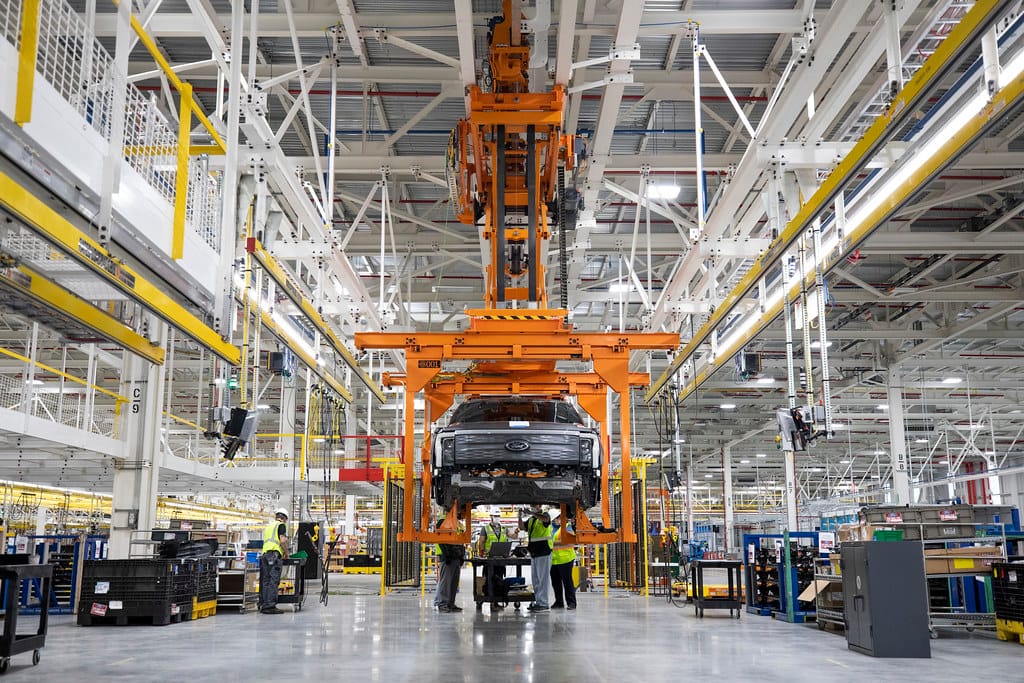

The push for an eight-hour work day has a long history in the U.S. Despite workers striking for an eight-hour day in the mid-1800s, it remained elusive for many. In 1914, Henry Ford to the unprecedented step of moving his workers to an eight-hour work day and doubling their wages. His factories’ productivity increased.

Despite Ford’s success with the eight-hour day and the numerous strikes for it throughout history, federal legislation governing working hours for laborers in private companies didn’t appear until 1916 with the Adamson Act, which largely just affected railroad workers. It took until 1937, with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act for most Americans to see a 40-hour work week.