We're on the eve of expected 25% tariffs against Canada and Mexico going into effect. Michigan and Metro Detroit's economies are deeply tied to international trade — whether it's the automotive and manufacturing sectors or our vast agricultural areas.

So what are we really looking at as far as impacts by the decision the Trump administration says they're going to make? How do we get past the rhetoric, fear, and doubt to how this will impact our state and region, as many jobs and livelihoods are on the line?

What about cost increases on everything from avocados to autos? What about gas prices?

If we decide to put tariffs on the European Union, how will that likely increase drug prices? What about the thought that "tariffs didn't hurt the last time?"

My guests are two experts, economists from Michigan State University.

David Ortega is a food economist and professor at MSU

Jason Miller is a professor of Supply Chain Management at MSU.

You can find Daily Detroit on your favorite podcast apps like Spotify, Overcast, Apple Podcasts and more.

Daily Detroit is brought to you by the community, support our work at patreon.com/dailydetroit.

Scroll down for a complete transcript.

Jer Staes: Hello, and welcome to your Daily Detroit for Monday, March 3rd, 2025. I am Jer Staes, and today's episode is going to be about tariffs and their potential impacts.

There's a lot going on in the greater story that could greatly impact Metro Detroit in Michigan, and I want to get past the fear, uncertainty and doubt. I want to have a level conversation about what we all can think about, prepare for on the eve of, you know, possible tariffs, and even if they don't get deployed tomorrow, they may be deployed in the future. I know that this can shift, but I want, I've wanted to have a conversation like this for a while, so we understand what's on the table.

And to help me do that, David Ortega, he is a food economist and professor at Michigan State University. Welcome to Daily Detroit!

David Ortega: Hi, Jer! Thanks for having me on.

Jer Staes: And Jason Miller, Professor of Supply Chain Management at Michigan State. Good to have you on, Jason!

Jason Miller: Hey, thanks for having me.

Jer Staes: Of course, of course. All right, let's do a Mother May I? basic setup here because there's a lot of talk about what are tariffs? What do they do? Who pays for them? I don't know who wants to take it first, but why don't we outline what a tariff actually is?

David Ortega: Sure. I'm happy to take a crack at it. So when we, when we're talking about tariffs, and it's something we've been hearing a lot over the last couple of months. So tariffs are essentially a tax that is imposed on imported goods.

And so a couple of things to keep in mind there is that it is the importer that is paying, the tax on, and it's on the value of the goods that we are importing. And so that's really important to keep in mind. So when we hear of tariffs of 10% or 25%, it doesn't necessarily mean that we're going to see the price of goods at the grocery store, or the price of, you know, other items go up by that 10 or 25% because a lot of the value and the cost of the things that we buy are accrued domestically here within the United States. So some of the transportation the wholesale markups, the retailer margins of food products at the grocery store, those are not subject to the tariffs. But basically tariffs are just a tax on imports.

Jer Staes: Depending on the industry, though, there can be different kinds of impacts, like specifically with the automotive industry where you've got parts going back and forth across the border, that could play a little bit differently as well, right? It can get complicated.

Jason Miller: It certainly can on that. And one of the big issues that has not, we've not received clarity yet even from the Trump administration, is whether there will be any what are called duty drawbacks for US manufacturers. And what that would mean as an example is, let's say I'm an auto parts supplier outside of Detroit. Let's say the third stage of a production process where I'm importing a good from Canada, refining it more, and then exporting it back to Canada.

Normally, you are allowed to essentially get a drawback on the duty that you paid for that import because you're exporting the product. But right now, there doesn't necessarily seem to be evidence of that, which would suggest that for parts that cross the border multiple times, we're going to have what we call a tariff pyramiding effect where we would be adding 25% on top of the value each time that product is imported to the United States.

Jer Staes: I can understand how the public could be very confused by this because I'm barely following. That's that's really interesting to look at. Now, when we're talking about, you know, food and goods like that, specifically, you know, because David, you're a food economist, this could have a multitude of impacts, not just because of the tariffs we impose, but also in retaliation, other countries that we interface with could and are probably going to put tariffs up as well, correct?

David Ortega: Yeah, no, absolutely. And this is something that we saw during our last trade war with China back in 2018. So when we're talking about these tariffs that we're imposing on China and looking at potentially going into effect tomorrow on our closest trading partners, Mexico and Canada, if they were to go into effect, they're not just going to sit back and say, okay, you know, now we have these tariffs. They're going to retaliate.

And Canada when these tariffs were announced, about a month ago, you know, they released a list of products that would likely face retaliatory tariffs. And these are just tariffs that they would impose in response to the tariffs that we are imposing on them. So when we saw what happened with China back in 2018, they hit our agricultural sector pretty hard. They imposed tariffs on our exports of soybeans corn, as well as some of our meat exports.

And just to put it into perspective, back then, the agricultural sector in the US lost about $25 billion in lost exports as a result of these retaliatory tariffs. So it can have a pretty significant impact on our food and agricultural system.

Jer Staes: You make an interesting point there because something I will often see in the discourse is that the last time there were tariffs, nothing happened. And I don't you're saying that's not true.

David Ortega: That's certainly not true. I mean, a lot happened and, you know, if you talk to any soybean farmer here in Michigan or or anywhere across the country, they'll very much remember the impacts that they felt during our last trade war with China.

Now, you know, it's worth pointing out that, you know, there was a significant loss in terms of the value of exports that were going to China as a result of these retaliatory tariffs, but the government stepped in and basically, you know, gave farmers that were affected support. I mean, to the tune of, you know, $23 billion plus to sort of compensate them for for lost export markets. But, you know, these are taxpayer dollars. And so, you know, definitely there was an impact that that the agricultural sector felt and that consumers felt, you know, last time we, we engaged in a trade war with China.

Jason Miller: No, and and building on that too, US manufacturers were negatively affected by the trade war with China. We buy a lot of goods from China that serve as inputs to products we manufacture here and that and then turn around and export.

And what some research has shown was that the manufacturers whose imported goods saw the biggest increase in tariffs, those same manufacturers saw bigger decreases in exports subsequently. And so the US economy the manufacturing industry saw a fairly sharp downturn in 2019, and a lot of that has been linked to price increases that they incurred due to tariffs.

Jer Staes: You made the point about the subsidies. One of the ideas behind these tariffs is to create a bunch of revenue for the government. It feels like it would be offset if we're having to create subsidies or provide subsidies or backstops to people who are losing business due to these tariffs.

David Ortega: No, and I mean, that's absolutely right. I mean, if math just doesn't work out, right? In terms of using tariffs as a source of government revenue.

And yeah, as, as we just discussed, you know, if you impose, if you impose tariffs on other countries, then they retaliate, and then you have to compensate stakeholders and sectors that are impacted by those retaliatory tariffs. You know, this is why these types of trade wars, sort of broad-based tariffs on our trading partners just, you know, don't make economic sense.

Jer Staes: Now, part of the goal of some of this is to encourage more things, more products, whatever to be sourced and and built domestically. What would be alternatives maybe to a tariff from a more sound economic point of view to if that is in fact your policy goal, what might be, and I know this is a bit of a thought experiment. What could be a couple of ideas that would be alternatives if you say, you know what, economically, I really believe more things should be made in the US outside of tariffs. What are some other tools that could have been used?

Jason Miller: So we've seen a lot of efforts, for example, in the advanced manufacturing space to take semiconductors. The very large grants that have been provided to Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturing, Intel, et cetera to build more fabrication facilities in the United States.

Now, this is not a silver bullet as well. We've already seen Intel just last week announce that they're not opening that chip manufacturing complex being built in Ohio until 2030. So they've delayed opening by at least four years. So that's one strategy. You see efforts to buy American provisions, especially for government investment projects and things like that.

But the real reality is goods where you are not fundamentally cost competitive anymore in the United States, it is very difficult to see much of a future in manufacturing large quantities of these products because the moment any type of support is removed, you're no longer cost competitive. A great example of this was the N95 five masks that were in such high demand during the COVID pandemic. If you look today, most hospitals immediately shifted back to sourcing from overseas and in particular from China because the cost is so much lower versus domestically made masks.

Jer Staes: So the genie is out of the bottle on this one.

Jason Miller: Yes, and that's I think the difficult thing for many Americans to accept. But when we liberalized trade, especially with China back in October of 2000, we let the genie out of the bottle. Certain manufacturing industries in the United States like apparel, making plumbing fixtures, making steel springs, et cetera, were certainly negatively affected by that.

However, it doesn't mean that putting tariffs on these goods is going to lead to a renaissance of production of these products. In fact, a good example is we put tariffs on Chinese furniture in October of 2018, and then in 2019, US domestic production of furniture fell 6%. And so you didn't see any type of reshoring bump. If anything, domestic production was hurt further.

Jer Staes: Wow. On the food side, David, there are things, I'm no expert, but I know that there are things that we just don't, I mean, I'm drinking coffee right now. There are things we don't, we just don't create in mass quantities in the United States, right? Like there's a gap here of nature.

David Ortega: Right, no, and I think that's, you know, the agricultural and food sectors and example, you know, of an industry and a sector where we rely on international trade. We rely on imports of food and agricultural products in order to meet year round consumer demand, you know, for these products. So like you pointed out, coffee, you know, outside of the state of Hawaii, there's very little to no coffee being produced in the continental United States.

So we look to our trading partners, you know, Mexico, countries in Latin America to be able to source, those products to be able to import coffee. When we look at fruit and vegetable products or produce a significant amount of our produce very close to two thirds of the produce that we consume, so fresh fruit and vegetables here in the US are imported. And a big bulk of that is imported from places like Mexico and to an extent Canada because they have different growing periods.

We import a lot of produce also from South America and Latin America. We're in the middle of winter here. We're sort of at the tail end of winter going into spring. We're not able to grow a lot of the food products that we are known for, you know, in our summer months. And so we engage in trade in part to be able to meet year round consumer demand.

Jer Staes: Yeah, I remember my grandmother telling me one time about how she grew up in a world where there were just things you didn't have at certain times of the year. And how thankful we should be. I know it's a little crazy, but my grandmother was born in 1909. And so she saw a very different world than the one we have. And that's not that long ago, to be very honest.

David Ortega: No, absolutely. I mean, it's, you know, a testament to the trade that we engage in with our partners that we can get tomatoes and peppers and avocados in in our winter months here in Michigan. Just to give you an example, so 90% of the avocados that are consumed in the United States are sourced from Mexico. You know, we had the Super Bowl a couple weeks back. We're seeing Cinco de Mayo is on the horizon. We depend on Mexico to be able to have a supply of avocados for those dates.

Jer Staes: One of the reasons I'm glad to talk to both of you is that, yes the supply chain management, obviously, people think about automotive and manufacturing, but on the other side, Michigan is actually a pretty big agricultural state in a lot of ways. We have a very big egg sector. So with both of you, and I think we can do this in series with both of you, I want to ask what will be or what could be some of the impacts right here in Michigan and Metro Detroit that we might not be thinking. I want to localize this conversation.

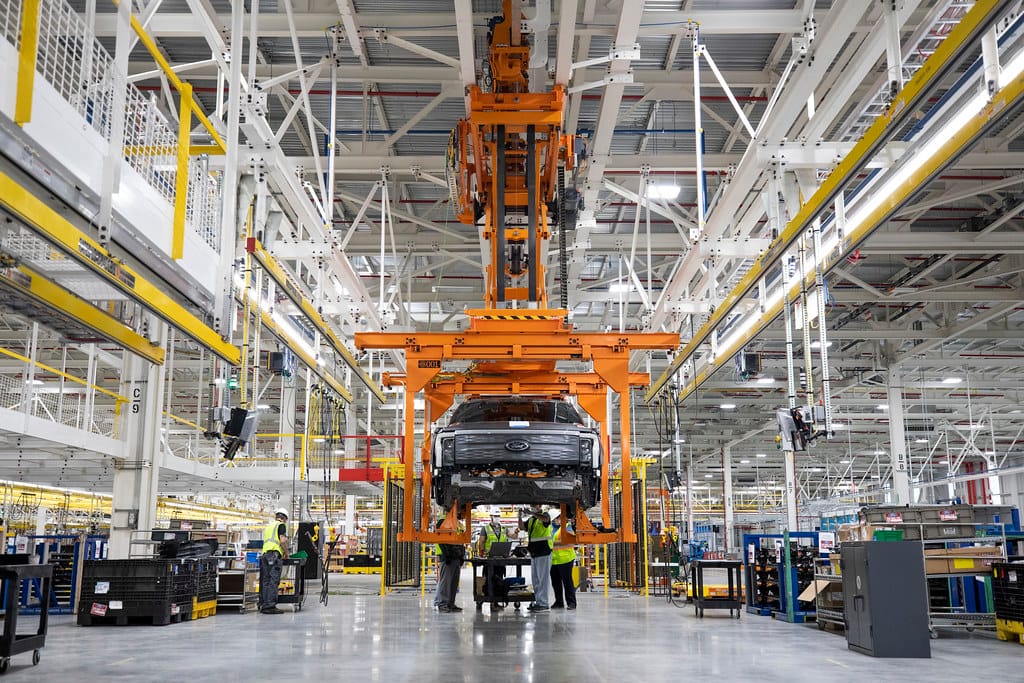

Jason Miller: So to me, the biggest concern for the entire Michigan economy just in general is going to be what effect does this have on motor vehicle and parts production in this state? And do we unfortunately see layoffs commence if the auto sector is as negatively affected as many of us are expecting.

And so to me that is the most immediate serious concern that I see. And also some inflation that would be likely as well. So just as, as David was mentioning, given the amount of fresh fruit and produce that we import from Mexico, especially there's almost no way that if tariffs are implemented here in March, that we don't see some inflationary effects and also the price of gasoline.

So most crude oil refined in the Midwest comes from Canada, the rough figure is 70%. Those refineries are geared to run that consistency of crude oil. We do not produce that consistency of crude oil here in the United States. Our crude is what's called light sweet, and the pipeline capacity is not such that you can essentially replace Canadian crude oil. So we're likely looking at some degree of inflation on gasoline prices as well once these tariffs would hit.

Jer Staes: I've seen some reporting numbers anywhere from $3 to $10,000 to the increase of a price of a of a truck. One thing and I saw that over the weekend, it really stunned me. It was in a couple of the papers talking about that $10,000 price impact increase. I didn't realize how much the pickup truck segment, which is super important to American automakers, is exposed to this.

Jason Miller: It is, it's massively exposed. And this is where, you know, as well as I was mentioning earlier, the parts that cross the border multiple times, if you have this tariff pyramiding effect, that's how you get these very large increases. And so you're talking $10,000, you know, cost increase, that is a huge, you know, a further burden on Americans at a time where we're seeing auto loan delinquencies at, you know, historically rather high levels. And a lot of that's due to the inflated price that was paid by consumers in 21 and 22 when we had the chronic shortage of vehicles.

Jer Staes: Now, on the agriculture side, what are we, what are we looking at? I think about crops like apples and cherry cherries, there's a bunch of things from Michigan that I think about. How could how could that kind of stuff be impacted?

David Ortega: Yeah, so I mean, you pointed out. So we are a very diverse agricultural state. So a lot of people like to claim that California is the most agricultural diverse state in the country. Well, here in Michigan, we like to say that we are the most agricultural diverse state with a reliable source of water, right? So agriculture is really one of the pillars of our economy.

So we have the cherries, the apples, we have beans, we produce a wider range of food and agricultural goods. So when we're looking at, you know, these tariffs potentially going into effect, they would primarily at first impact consumers at the grocery store. You know, we import here in Michigan over $3 billion of food and agricultural products. That's the number from 2024, half of that attributed to Canada alone. Again, these are just Michigan food imports.

And as Jason was mentioning, and we've talked, we've been hearing and not just hearing, but we've been feeling the effects of increasing food prices. So food price inflation is something that, you know, we've been dealing with ever since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that rate of increase, which is what inflation really captures has come down and it has moderated.

And so what we need now is just a period of stability, and in particular, you know, when it comes to these policies that are going to very likely if not, almost surely, have the complete opposite impact and that is that instead of bringing prices down, they're going to increase food prices. But then on the other side, you know, if we see retaliatory tariffs and we engage in a full-blown trade war with our closest partners, Mexico and Canada, and even China, like we saw last time, and you know, it's very likely that they're going to target our agricultural sector and that would just have devastating consequences and impacts to to our farmers and and the agricultural and food industry as a whole in the state.

Jer Staes: I hate to ask for a little preview of things to come, but there's also talk on the table of tariffs against the EU. I you know, I know we don't have tons of time to go into all the details, but what are a couple of thumbnail things that could be affected if we also put up similar tariffs to the European Union?

Jason Miller: Pharmaceuticals, pharmaceuticals, pharmaceuticals. So the EU is a massive supplier of pharmaceuticals. One of the biggest trade deficits the United States runs is with Ireland, which is a pharmaceutical producing powerhouse. And then motor, motor vehicles, machinery, things like that. And certainly a decent amount of, you know, beverages, so wine, beer, et cetera.Mhm.

But the kind of the big outsize effect with the EU is that pharmaceutical sector.

Jer Staes: So this would encourage drug prices to actually go up instead of down.

Jason Miller: It's not going to help.

Jer Staes: Okay. David, do you have anything to add on that?

David Ortega: You know, on the sort of food and agricultural side, you know, we import some processed fruit and nut products from from Europe, but as Jason was saying, you know, this is going to hit your French wines or Italian wines. So, you know, you can expect those to sort of go up in price if these tariffs do go into effect with our European partners.

Jer Staes: And then some retaliatory effects, I assume as well. Like in the Canadian discussion, there was a lot of talk about bourbon. I don't know the European demands for certain US goods, you would of course know more than I do.

David Ortega: Yeah, so, you know, we could expect retaliatory tariffs. A lot of that is really going to depend on, you know, which sectors, which products will be the target. And I think with this whole discussion in general and this issue of tariffs, there's just a lot of uncertainty right now.

From the US side, there's been a lot of threats and sort of changing off of certain dates when these things are going into effect, but there's just a lot of uncertainty. And even that uncertainty is just not good for business. It's not good for the economy. It's not good for food prices. And so, you know, there's, a lot that we still don't know, about how this is going to play out.

Jer Staes: I was going to mention, this seems to be a theme through this and listeners may or may not know, I used to work in in the business world, and I've seen that oftentimes businesses can adapt to things, but it's the uncertainty, it's the not knowing how it's going to roll out. There were some things in this conversation are very concerning to me about not knowing the details, you know, we're talking about the the automotive sector, that has got to be maddening for a company trying to fig figure out who are they going to hire, who are the who do they got to let go, plant predictions, all that kind of stuff.

Jason Miller: It is, and we're actually starting to see effects of this in the economic data. Just this morning we received the Institute for Supply Management's purchasing manager index, which is a very good predictor of where manufacturing is going. And February showed a sharp drop in the upward momentum of new orders. So new orders went from expanding strongly in January to contracting in February. And the respondent comments are mostly about tariff uncertainty. One thing we are seeing though is substantial evidence of price increases already, and these tariffs have essentially only with China went into effect as of this instant in time. But we're already starting to see a lot of reports of cost inflation.

Jer Staes: Well, David Ortega, food economist and professor at Michigan State University and Jason Miller, Professor of Supply chain management. Both of you, I really hope at some point we find some way to have a conversation about something joyful. But I really appreciate both of you spending the time on this. It is an important topic to talk about. And I think I really appreciate you both taking the time to unpack this for our listeners because it's so important and it's going to have so many real impacts on the ground for people's daily lives.

Jason Miller: Yeah, thank you for having us.

Jer Staes: Three things before you go. Number one, we are up for Our Detroit's best podcast 2025. Go to ourdetroit.com. We could use your vote. It's absolutely free and we'll help get the word out about our show. Number two, episodes like these are funded by our members on Patreon. I'll be honest, advertisers do not want to touch episodes like this. So your support is necessary for local media. Local media needs local support to survive. So patreon.com/dailydetroit. And if you haven't already, share Daily Detroit with a friend. Word of mouth is the best way to grow the show. With that, I'm Jer Staes. Thank you so much for listening! Remember that you are somebody, and we'll talk tomorrow.