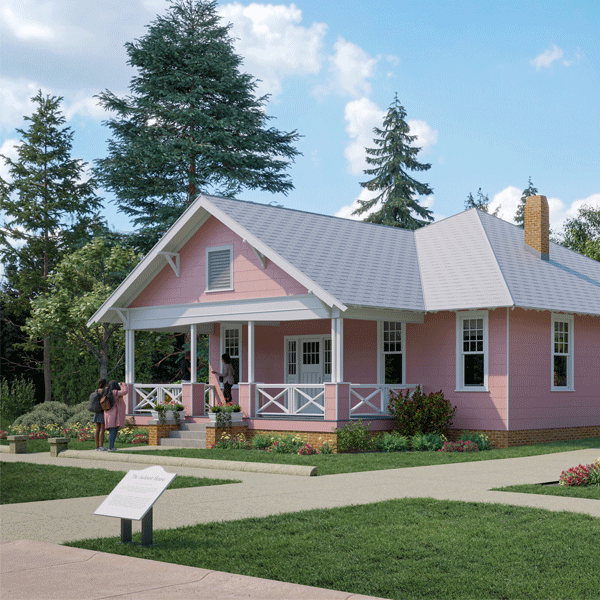

The Jackson Home, originally in Selma, Alabama was a crucial place in the fight for true freedom for African-Americans.

It's been moved here to Metro Detroit at Greenfield Village in The Henry Ford, so that it can be preserved, celebrated, and the story told.

So I went to Dearborn and talked with the Curator of Black History at The Henry Ford, Amber Mitchell.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson and Mrs. Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson offered their home as a sanctuary and strategic hub for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights leaders as they planned the marches that ultimately changed America.

From the Jackson's living room, Dr. King and others watched the “We Shall Overcome” speech by President Lyndon B Johnson… publicly backed voting rights.

The Selma to Montogomery March was planned there, and all of this culminated with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

So get all the details. Why it's here. What's happening with the progress. What kinds of programming are they thinking, and of course, the importance of this work being done today.

More at the Henry Ford: https://www.thehenryford.org/visit/greenfield-village/jackson-home/

Follow Daily Detroit on Apple Podcasts.

A full automated transcript of the conversation is below. Please check against the original audio when quoting.

Thanks to our members on Patreon, who got this conversation yesterday. Local media requires local support, and thanks to Kate and Jade for supporting us recently. You can join them.. Get early access to episodes, our off the record, off the rails podcast, swag and more at patreon.com/dailydetroit. We even have an easy, one-time annual option now.

Transcription of conversation with Amber Mitchell

Jer Staes: When I first heard that you all are bringing a house up from Selma, Alabama, I was, one, amazed. Two, I think what an excellent act of trying to just keep the spirit alive of the spaces that I think sometimes people forget about. So, why don't we start with the very basics? Let's talk about this house and why it's so historically important.

Amber Mitchell: Sure. So, the house that we're talking about is the home of Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson from Selma, Alabama. The two of them. Dr. Sullivan Jackson was a dentist. His wife, Richie Jean was an educator. They both took a very personal and direct action as it relates to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Specifically the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama that at its height in 1965, they opened up the doors to their long time friend, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And they basically became the home base for that organization in Selma during this time.

So from January to June of 1965, Dr. King, amongst many others, lived and worked inside of this home, planned out the basics of the Voting Rights Act and as well as planned the Selma to Montgomery march. And I think for a lot of people, what they might remember most about that particular event or series of events is Bloody Sunday. And that is the march or attempted march from Selma to Montgomery that took place on March 7th, 1965, led by now former Congressman John Lewis and Reverend Hosea Williams, where they led people across the infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge, to which they were met with the force of the Alabama State Troopers. And so those images have lived in the American mind for — really the international mind for the last 60 years. And so we're at this particular really interesting moment in 2025 where we are recognizing … acknowledging the 60th anniversary of all of those activities leading up to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I think it's interesting to highlight the work of the helpers, especially in this time. You think about — you know, I've been to the Hotel Lorraine in Memphis and other places. But all these movements, I'm not saying that that hotel was like the luxury of anything, but all these movements really started with [the] community working together. You mentioned that Dr. King lived in the house. That was kind of common with the movement at the time, right? People helping each other.

Amber Mitchell: Absolutely. That is core to not just the Selma movement, but all of all aspects of community based movements. It is rooted in people doing the work on the ground. And in fact, SCLC when they come into town in January of '65, they are kind of late to the game. There had been several decades of activism, both successful and unsuccessful, in the Alabama Black belt where Selma is located. And so, you know, two years prior, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or SNCC had come in first and done some on the ground grassroots activism.

But all of that could not have been done without a direct activism from the people of Selma and the surrounding area, specifically led by the Dallas County Voters League, and their team of the Courageous Eight, of which probably the most famous person on that team was Amelia Boynton [Robinson] who again, that Bloody Sunday imagery of people being picked up by their comrades in the streets and taken back across the bridge. Mrs. Boynton is one of those people who is on the ground and she's in her 50s at this point, 40s, 50s at this point. Another person who's part of the Courageous Eight is Miss Marie Foster, who is actually Dr. Sullivan Jackson's sister. She also was his dental hygienist in his practice. And so if it wasn't for the work of these people, SCLC would not have been able to come in and do what they were able to do. As well as working together throughout those six months to get the Voting Rights Act not only just brought to the table, but ultimately passed in August of '65.

So how does this Jackson house fit into the rest of the streets of Greenfield Village? You don't add houses willy-nilly. You don't just add things whenever. There's a breadth of buildings. You've got the bicycle shop. You've got, you know, the old factory. You've got things — I remember, you know, looking at things where, you know, the Corktown neighborhood of Detroit, all these things. But it's an intentional move to add anything to the street. Why is it so important to add the Jackson house to the streets of Greenfield Village?

Amber Mitchell: Absolutely. So we were approached in 2022 by Miss Joanna Jackson, the sole daughter, sole child of the Jacksons, with the intention of looking for a place to steward her family's story. She had been doing that for her entire life but realizing that there needed to be a succession plan. There needed to be a way for not only for the home and all of its contents to stay together, but for it to be taken care of in perpetuity. And I think she recognized that the Henry Ford is a place that not only do, you know, millions of people come to see what we have in both the village and the museum and other aspects of what we do here, but also that um that space would be taken care of and uh treated with respect.

And so, you know, like you said, we don't just move houses willy-nilly. It's a very intensive process. It was not taken lightly. We didn't go out and basically try and acquire this home. This is something that — an opportunity that was brought to us and we've tried to maximize that. And so the house itself is going to be in our porches and parlors district. So this is the area where we talk a lot about home life and what does life look like for Americans, you know, both from the 18th century all the way up to when the Jackson house opens, it's our — probably our most — what's the term I'm looking for? Excuse me. It will be our most recent uh sort of interpretation at 1965. So it'll be a huge jump for us from our current houses that kind of stop around 1930 to going into the mid century, going into living memory that we have right now.

The thing that gets me and I think about this more and more as I get older, is like, wait a second. 1965 was a minute ago. Right? You think about it as, oh, well you maybe see the show Mad Men or something like that. I was like, wait a second. 1965, we are truly talking 60 years. It's wild.

Amber Mitchell: Right. It's 60 years, and it's interesting because it feels far away, but it's not that far away. Like, you know, in doing this research and pulling resources, pulling images, going through archives, talking with movement veterans who were there, who experienced all this, you know, they have a very vivid memory of these activities. They have a very vivid memory of being yelled at, being chased by dogs, being hit with water cannons. They have a very vivid memory of what life looked like before what before these gains that were made for us.

And really as of right now, it could not be more relevant, right? You know, we often think about it, you know, as, you know, time moves forward, things tend to stay the same. And in fact, we're in this real interesting microcosm of change and transformation and re-looking at the past to make sure that we're understanding its power for the present and hopefully not having to fight those same battles over and over again, right? And so, you know, here at the Henry Ford [Museum], you know, using the past as a tool to move forward is something that we do every day. And we're really excited to be able to talk about a uniquely American story through the Jackson Home project.

How important is it to capture these places and these conversations while they're still at the edge of living memory? Because I think about all the stories through time that have been adjusted by history. Before we started recording, I was mentioning uh about moving houses and the U.S. Grant house was moved in Detroit. Well, the story of Ulysses S. Grant was extremely altered through time and frankly, in my opinion, given a pretty bad rap in a lot of ways because of backlash. So how important it is to capture these stories now because I think in the past there wasn't that ability to be like, hey, here's a video of this. Hey, here's the place that it was. Hey, we're going to take care of it now so that we have an accurate representation of what actually happened.

Amber Mitchell: Yeah. I think for stories of people of color, but especially stories of African Americans, with it throughout our history of the United States, history in and of itself is a practice of power for a lot of folks. Who has the ability to tell the story? What story is being told and who's left out of that story. And so for myself as a historian of African American history and curator here, it's really important that we not only talk to those who were there, and we make sure that we get their stories down from their perspectives, but we also are using that in conjunction with histories that have been written and those that have maybe been forgotten over the last several years.

You know, I think for a lot of folks — you know, they might not have time to sit down and read a huge thousand word page book or a thousand page book, excuse me, on say the life of John Lewis, which there's a very new book out that is very good and I would highly suggest reading that thousand pages. But if you don't have time or you don't have that ability, what you can do is maybe go to a museum. What you can do is maybe listen to an oral history. What you can do is maybe read a blog post on that museum's website. I think what we do best as museums and historic sites and other public history spaces is make sure that history is accessible for folks at any and all levels, so that they can best understand the world around them, give themselves context and critically think about how this truly affects them today and hopefully um do something with that energy.

I love reading books. Do not get me wrong. But there is something about experiencing the space, like the times I've been to the Henry Ford and learned new things or even like I think about, you know, it's almost cliche but the Rosa Parks bus, right? When you sit in the bus and be quiet and you experience a moment or you go to oftentimes you've got the slave housing. Sure. Yeah, the stories around that or even on a lighter note, the old-timey baseball. The experience makes it extremely real in a way that will connect, I think with anyone and even the most hardened hearts.

Amber Mitchell: Absolutely. So, you know, people learn best through doing. And there is a certain power in place and being in a space where a certain event happened. You know, there's — like I mentioned, this is a very well-documented event. The events of 1965 leading up to the Voting Rights Act. We have video, we have photos. But to be able to be in the space where that photo was taken, surrounded by the artifacts that were also being used by those same people 60 years ago, it's a transformative experience.

There's real power when you walk into those places, and an ability to not only just change your own experience for that day, but potentially change your life and the way that you understand the world around you. And so, you know, the Henry Ford, is a wonderful place to be able to do that and we are really looking forward to being able to bring people into a new way of understanding our collective story through the Jackson home. You know, for example, in that particular house, you know, Miss Richie Jean, her whole thing was about making sure that there was a place of rest and respite for the movement makers, right? We tend to think about those folks as almost like freight trains. They just keep going and going and going. They're human beings. They're people. And in that space, she let them be just individuals and people and rest. And she, you know, she would cook and make sure they had a place to stay, a good food to eat, um a safe place to to get prepared for the next level of activism that they needed to do because that's an important part of making sure that we're able to fight and continue to fight the battles that need to be fought.

Well, it may seem counterintuitive, but rest is resistance.

Amber Mitchell: Rest is absolutely resistance, you know, Rest is absolutely resistance. You know, if you haven't read the book by Trisha Hersey, shout out to her. Rest is resistance is a powerful tool and you cannot do the work that needs to be done without getting your rest.

I know listeners want to know a little bit about the brass tacks. Of how on earth you got this thing up here. And what size are we talking about? Like square footage-ish and how did that get up here?

Amber Mitchell: Sure. So the house itself is about 2,000 square feet. It's built in 1919 and designed by Wallace Rayfield, who is the second licensed black architect in the United States. He kind of builds the entirety of of Black Alabama. So from Montgomery to Tuskegee to Selma and other places in the city, I mean, excuse me, in the state, he really leaves a footprint. The house in of itself, the way that we ended up doing is we took everything out. So all of the furniture, all the things that were left by the family that we received in our acquisition, were packed up very, very, very delicately and very time-stakingly, and brought up here, shipped up here. The home in of itself was braced inside. The roof was taken off. The porch was taken off. Basically the windows, doors, all those things were packed up separately and shipped up.

And then the home was essentially cut in half and basically packaged within a waterproof for lack of a better term, trailer and brought up in two halves. So it drove one each half drove 900 miles from Selma to Detroit over the course of about a month or so. And then each half because we had to use the same team for the two halves. It was stored offsite at a facility for a few months as we prepared the foundation for the home to go on in its final place on Maple Road — Maple Lane, excuse me, in Greenfield Village. And then it was brought in those two halves. One was placed on one side, the other placed on the other side of the foundation. And in fact, we had an excellent team of absolute experts, who have not only just been with us since the very beginning, but continue to work with us to bring the house to fruition. And so in fact, I just have to say, you know, we had a gentleman who drove the two halves of the houses up. He's about 25 years old, and when I tell you he whipped that house around like a F-150 backing it up onto his place on Maple Lane, I am not kidding. He got it. He got the second half literally within the sawblades width of the way it was cut down the middle of the home. So it was an amazing, amazing project.

Shout out to our truck drivers.

Amber Mitchell: Shout out to truck drivers. Go UAW! Go you know. Go Teamsters, everybody, you know, shout out to those who have the skills because I don't have them. Right? I'm a historian. I'm a curator. I read. I write. Let me talk to folks. Let me explain stories. Ask me to drive a truck. You know, if it's too big, we just not going to move. So, you know, it's this project, the level of specificity, the level of expertise and the level of pride that has been taken and making sure that, you know, you don't you don't move a home lightly.

This isn't something that we just set out to do, you know, when we were approached by Miss Joanna in 2022, this is something that we had to do real extreme, not only just soul searching as an institution, but making sure that this is something that we were ready to do. And fortunately, we have the folks here who know how to do that kind of work. And if we don't know, we know how to get in touch with those who know how to do that kind of work. So, it's been a really amazing project and it's not done at all anytime soon. Luckily, you know, we are still in the process of the roof actually just got put back onto the home.

We're recreating the 1965 look of the front porch because of course this was a house that was lived in. Right? Well beyond our period of significance of 1965. And so, you know, if you think about how many times have you maybe re-designed your kitchen or painted your walls or maybe redid your backyard. This is the same thing. This is a house that was lived in until about 2013.

And so what we've had to do is this really interesting historical detective work that has been a mix of oral histories with family and friends and people who have experienced the house firsthand, obviously using Miss Richie Jean's book, the House by the Side of the Road, as well as looking at family photos to trace back what did this front porch look like? What did the house look like? And so again, we have real experts here on staff that have been doing this work, getting down to what some might think as minuscule details about, well, what kind of carpet was in this house? What color were the wallpaper? What color was the wallpaper? What kind of perfume did Miss Richie Jean wear? What kind of cigarettes did Martin Luther King smoke? You know, these — down to these little things that we can use to help tell these deeper stories, to make these people human and make this history real.

I think that's so important. You know, it takes a village to make all these things happen. You said it's going to be a minute, but how long are we looking at for a timeline in Greenfield Village for people to experience this? You have an idea.

Amber Mitchell: Yes. Yes, yes, yes. So the home itself will be open in summer of 2026. So likely this is going to be, we're probably going to have a big, not probably we are. Let me stop saying that. We're going to have a huge splash — grand opening event the weekend of June 10th through 14th of 2026. There's going to be so much going on um and we're still working through what a lot of that looks like. But we also realize that there's going to be a lot of people who want to see this home. Not just people here in Michigan, but folks who are constantly learning from the history of the Civil Rights Movement, folks both from Alabama and all over the country and folks internationally who are inspired by these stories. Um, and of course, this home isn't going anywhere. It is going to be here for the rest of our life as an institution, which hopefully is another 100 years, 200 years from now, but it'll be well taken care of and be able to inspire the next generation of movement makers and change makers in this country.

So when somebody comes down to Greenfield Village this season, they will be able to see what some of the exterior — like in the process work. You'll know it's being worked on.

Amber Mitchell: Yeah, exactly. So it, you know, last season when it was installed, it was basically two giant green blocks, green rectangles that were sitting on Maple Lane just in between the George Washington Carver Memorial and McGuffy Schoolhouse. This year it is unwrapped. Right? So they will see the exterior of the house, and the process of rebuilding a lot of this stuff. So they will see the rebuilding of the front porch. They'll see the install of the driveway because we're putting a driveway in. Um and they'll also see the building of our annex space at the back of the home. This space will allow us to tell a deeper story about the house.

There were over 8,000 artifacts that come out of this particular home acquisition, which is a mammoth undertaking for us. Usually we get about 4,000 artifacts per year that we process here. So we essentially have a small Jackson home only team who is just working on this project.

But we also recognize that there's going to be a lot of people who, beyond maybe Bloody Sunday, if they know that, they don't know really anything about the context of the Voting Rights Act, the Voting Rights movement and how it fits within not just American history, but civil rights history. And so that space will allow us to tell that deeper story before people enter the home. And so they'll see that being built as well.

We'll also have a number of different events that lead up to the opening of Jackson House. We have a blog series on our website right now at the Henry Ford.org that's exploring different aspects of the history of the Jacksons, of Selma, of Voting Rights and of course of the work that we're doing here. Things will also continue to be populated on all of our social media platforms, YouTube, various other things that we're doing right now.

I think if folks decide they want to come out to the museum. We do have an exhibit that has just opened up in the last couple weeks, that is an introduction to the Jacksons and the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act called “We Shall Overcome.” It is right next to our um your place in time exhibit just across from where uh our kind of flexible gallery spaces is on the museum floor. And there's a number of artifacts that came out of the home that are out on display as well as information about the Jackson Home and a video about the Voting Rights Act. So, there's a lot to do uh starting right now to learn more about the Jacksons, to learn more about the Voting Rights Act, um and of course to stay involved with the Henry Ford.

Well, and people forget, this is the number one tourism draw in Metro Detroit.

Amber Mitchell: It is. We are the largest or one of the largest museums in the Midwest and one of the largest in the country. You know, especially Greenfield Village, I don't think there's really any outdoor historic space that really competes with us in terms of the number of buildings. We have about 85 different buildings outside in Greenfield Village, all historic, whether they be historic businesses or historic homes that allow us to explore those places and spaces that have changed America or maybe just are interesting to you and your family. And of course, there's always the carousel and the Model T if and of course Thomas the Train when he comes in May. So, you know, it's always a good time here at the Henry Ford, but it's also an educational time at the Henry Ford as well.

I appreciate you so much. Thank you for your time on Daily Detroit. I really appreciate this conversation.

Amber Mitchell: Wonderful. Thank you, Jer for your time as well.